Mr Bunt, the Hare

comad August 7th, 2015

digitised from an original

Badminton Magazine of Sports and Pastimes

(date unknown)

MR. BUNT THE HARE

by Lilian E Bland

It had long been one of my desires to have a hare as a pet, and in the beginning of July the garden boy informed me that he had a young leveret out in the potting-shed for me. Imagine my delight when I saw the sweetest baby hare, only a day or two old, crouching very silent in the bottom of an old butter box. He was a reddish-brown ball of curly wool; his small black-tipped ears were lying flat on his neck; a little white star decorated his forehead, and the enormous eyes were rimmed with pale yellow. I at once removed this treasure from the box, and tucked him inside my coat, where he seemed to appreciate the warmth.

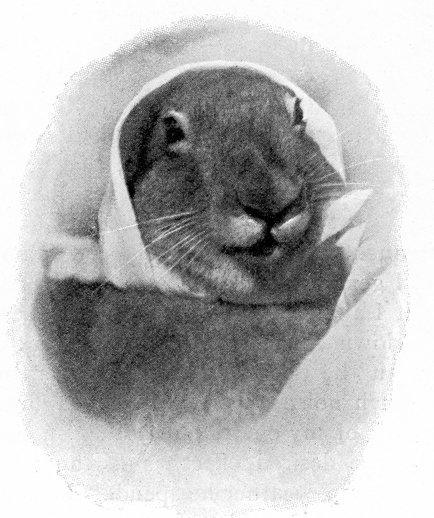

Very soon Mr. “Bunt” became quite at home, and sat up to eat clover out of my hand; and to watch him eating was delightful, he was so dainty and precise about it. Each leaf-stalk was folded back between his teeth so that he grasped the base of the trefoil, first, then when the leaf was finished a quick nibble (just like a seamstress biting off her thread) would sever the stalk from the main stem, which he never ate. Next to clover he preferred rye grass, and here one realised the object of folding the stems and eating them backwards, as the spiky flower-heads then came smoothly between the teeth, and the two ends at each side of his mouth would disappear with astonishing rapidity. I found that he did not know how to lap milk, so I converted a fountain-pen filler into a feeding bottle, and he sucked this with much relish, making the most delicious face afterwards as he licked his lips all round with a little pink tongue; then he always sat up to rub his nose, first giving his paws a quick little shake, like a cat when she wets her feet.

At first he was never put in a hutch, but spent the daytime in my pocket or, sitting on my lap. He loved to be stroked and petted, and would often lie stretched full length, like a dog, with his head resting on his paws. At night he was loose in my room, and the first morning I was awakened at dawn by a great scampering; this was Bunty tearing round as hard as he could race in circles, figures of eight, in and out, turning and twisting, with a shake of his head bucking off all fours, turning in the air and coming down in the opposite direction. But the moment he saw that he was observed he stopped; even now, if I want to watch his early morning exercises, I must do so with caution.

From the first I weighed him every four days. On July 14 he weighed 12 ounces (340 grams), and I found that he steadily gained one ounce in the twenty-four hours until August 30; after that he gained at the rate of four ounces (113 grams) a week, gradually decreasing to half an ounce per week, his present weight being 6 pounds 11 oz., ( 3 kg ) on December 22.

But to return to his babyhood. When he was about a fortnight old, he one day refused his bottle, and told me clearly that he considered himself grown up; and on being given a saucer of milk he lapped it in a most business-like fashion. At first he made a fuss if I did not give him cream; now he prefers milk; water he refuses to look at. As a baby he made me waste hours of my time crawling about the floor after him whilst he played hide-and-seek, pouncing out at me and then doing rings round me in a series of bucks; and when in mad spirits he tears round, with his scut unfurled in a straight line with his back.

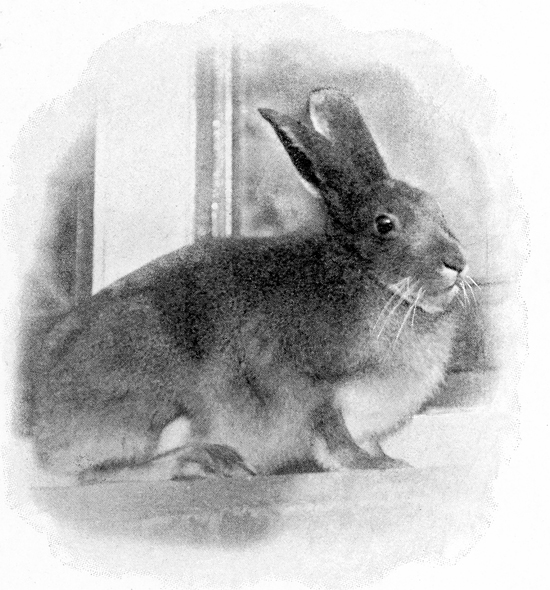

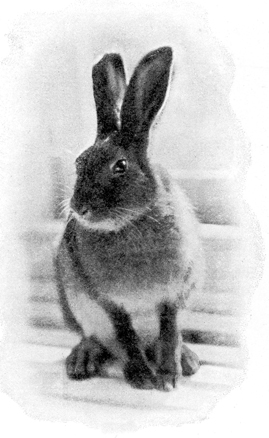

Bunty developed very rapidly, both in size and character. Physically his ears grew more rapidly than the rest of him, and assumed enormous proportions. He also showed possession of wonderful jumping and climbing propensities. Morally he is very obstinate, his motto being, “If you don’t at first succeed,” &c.

The first time I noticed this trait was one morning that he tried to jump up on the bed, and fell back with a thump on the floor. Instead of being discouraged he went a little farther off, took a running leap, and failed again. The third time he gave a tremendous buck off his hind legs, and landed fairly in the middle of me! After this he was so proud of himself that he repeated the performance every morning.

This was, however, only the beginning at his jumping career; each day he tried something higher, until he could buck four feet straight up on to my dressing-table, where he used to admire himself in the looking-glass, unless he saw me watching him, when he always pretended to be looking out of the window. The kick back of his hind legs as he left the table I could have admired in a hunter, but it had a disastrous effect amongst the objects of a rather crowded table.

One morning I was aroused by a fearful commotion. At first I thought he had climbed up the chimney; then by a frantic scrabbling I traced him to the inside of a tall clothes basket; he had jumped on to the lid, which had turned over and deposited him inside. The next morning exactly the same thing happened, so I waited to see what he would do, and he very soon managed to upset the basket and hop out. Of all animals he is the most inquisitive: he must examine everything: if it is an alarming object he advances cautiously, with outstretched nose, creeping along, and ready to turn and fly. His curiosity frequently gets him into trouble, more especially when he lands on all fours in the middle of my printing inks.

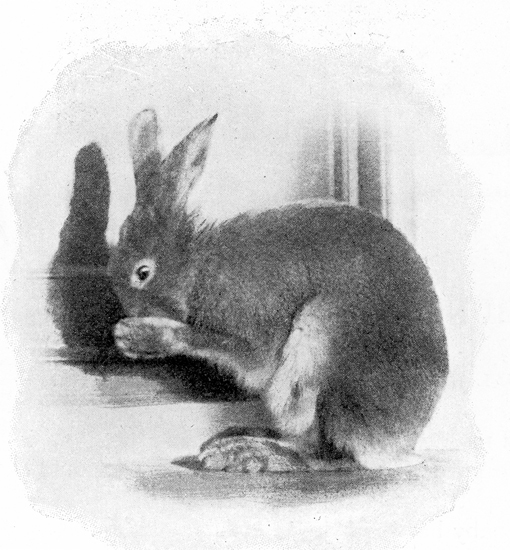

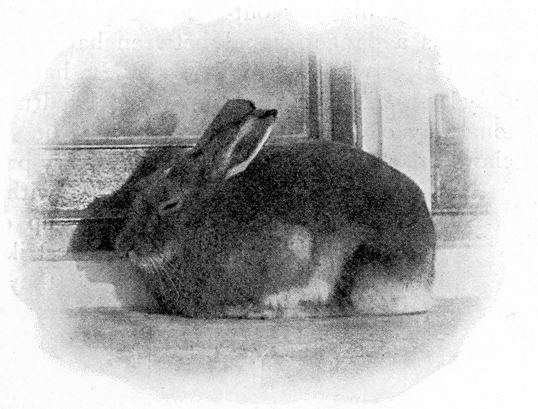

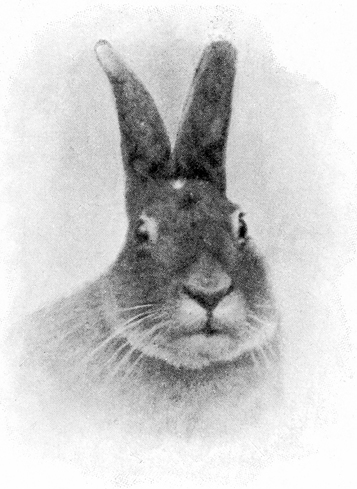

A hare is one of the cleanest animals in all its habits; and Bunty is most particular about his toilet, licking his fur just like a cat, and being most careful of his feet, each toe of the hind foot being stretched out separately while he licks between them, and his ears are pulled down with one pad and held in position for a minute inspection. Before Bunty showed me, I did not know how a hare squats in her form. First, then, you sit down squarely, hunch your back; and meditate for a while; then, if all is safe, you raise your fore feet, and pressing them firmly against your “lower chest” you tuck it in and drop on the point of your shoulder blades. In this position a hare’s legs and pads are kept warm and dry, and he squats in the smallest space.

In summer I tried to get Bunty accustomed to a light collar so as to be able to take him for walks. He did not mind the collar until he felt a check on the string; then he became perfectly frantic and would dash over and into anything, alarming me so much that I had to give up that idea. I suppose the instinct of centuries of snared hares was too much even for his common sense, and he would tremble and pant for long afterwards – for a hare, as I soon discovered, is a bundle of nerves.

Like most rodents, a hare’s teeth grow very rapidly, and they require something hard on which to file them down. I give Bunty logs of wood to gnaw, and he also likes an old brick to sharpen his teeth on; for his digestion he eats mortar, coke, earth, in fact grit of most kinds.

The first time I took him into a greenhouse with a cinder floor he surprised me by rolling like a horse. Cats and dogs, when they roll, wriggle about on their spine, with the back of their heads touching the earth; but a horse and all its relations put their heads down sideways and roll partially or entirely over; and a hare does the same thing. I took the hint that Bunty gave me, and provided him with a sand bath, which he rolls in every night.

One day a hollow cardboard box happened to he on the table, and Bunty sat on it and promptly started to drum. He made the most appalling noise, his fore feet working like lightning; no camera shutter would be fast enough to photograph the action, and given a good hollow box I would back him to “out-drum” any Orangeman! No doubt drumming is a danger signal between hares, like the double thump a rabbit gives with his hind legs, and a hare’s hearing is so wonderfully keen that the vibration made by drumming would be heard a long way off. Bunty drums on me if he is frightened, and as his claws are as sharp as needles it is very painful. Hares also fight with their fore feet, sitting up, on their hind legs and striking out rapidly as though they were boxing; also they make good use of their teeth.

Bunty often sits up and boxes with me in play, and he will hit a ball of paper on the end of a string backwards and forwards between us. He occasionally gives me a gentle nip, but reserves a hard bite for a stranger who tries to hold him. In winter Bunty’s diet consists of oats in the stalk, apples – which he loves – carrot tops, grass, &c.; and in September he eats grapes and vine leaves, a luxury which I did not encourage, but I believe in Germany the hares live in the vineyards.

Mr. Bunt is a very methodical person, and frequently gets annoyed with me for not being the same. For instance, I genera1ly take him up to my room at ten o’clock every night, but if I am later he gives me no peace. He jumps on the table, and sits down squarely on whatever work I happen to be at. I remove him, and he does a steeplechase over the tables and chairs, making as much noise as possible. As a final resource, he springs on to the back of my chair and drums on my back; this last move always has the desired effect, as it cannot be disregarded in comfort. In this damp weather he spends the daytime in the cold greenhouse, where he has made a form, and sleeps until evening; when he becomes lively, for the evening and early morning are his hours of play. Fortunately at this time of year the sun rises late, but I have become so accustomed to the noise that it hardly disturbs me; I always know that he has been exercising by the state of the carpet, which is rucked up into waves.

Every night it is etiquette for me to chase him round the room for at least twenty minutes, the game being a variation of hide and seek and catch-me-if-you-can; it is really rather exhausting, but capital exercise. There are certain corners where he allows himself to be caught, in fact he bounds into my arms; then he is plumped into the middle of the eiderdown quilt. If he is out of breath he sits up and boxes, otherwise he does a series of bucks, ending with a flying leap on to the floor, frequently over my head. After the game is over he sits up and begs for his milk, and he eats his food during the night. I have noticed that he cannot see in the dark by his not being able to judge distance properly in jumping on to or off the floor.

Bunty is a very charming and intelligent person, but one of his best qualities in my eyes is that he will not take any notice of anyone else. He dislikes men intensely, women he is less afraid of, but he is wild with all strangers. I had to go to England this summer and leave Bunty with the garden boy, who is devoted to animals. He took the hare to his home, and I received weekly reports, some of them delightfully quaint.

Mr. Bunt settled down in his new quarters after the first two days, and apparently made slaves of the family; one letter stated, “Mr. Bunt now sits on my knee and toys with my watch-chain.” When I returned his guardian handed him back with a sigh of relief. No hare had ever been so well cared for before, but it was a great responsibility. Bunty from the moment he saw me, although I had been away five weeks, took no further notice of the boy, which I think was ungrateful.

Sometimes I am almost sorry now that I know the hare folk so well. For one reason, jugged hare will never be my portion again, and it was very good; but there are other reasons far worse to think about, the coursing and snaring. I have, thank goodness, only been to one coursing meeting, the biggest in the north of Ireland, the Massereene. The hares were all in a pen, and they were driven out through a narrow run; there was only one way for them to go, straight up the park; as there was a wire fence on one side, and double lines of spectators on the other, the hares had no chance of escape. It was a most sickening sight, and how anyone can call this kind of slaughter sport, passes my comprehension.

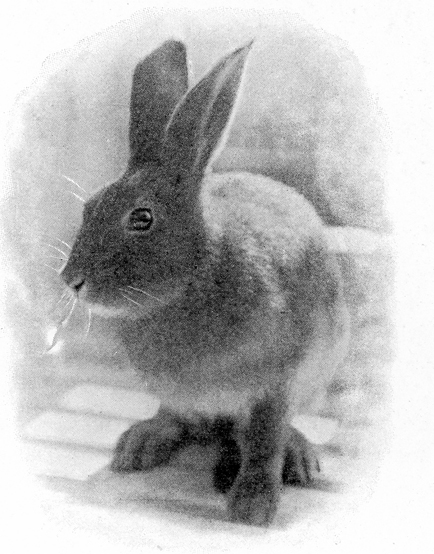

“WHAT SHALL I BE UP TO NEXT?”

There must always be a certain amount of cruelty in all hunting, but at least let the animal have a fair chance and fair play. I have often hunted with harriers, and there is no prettier hound work; but the odds are in favour of the hares; also, when they were killed, which I always regretted, they were decently killed; there was none of that horrible screaming of a hare torn between two greyhounds. I would have made coursing illegal long before cock-fighting, because I think it is far more cruel. It is the nature of cocks to fight, and they would do it of their own free will; of course the artificial spurs are abominable, but otherwise the cocks are equally matched in every way. I do not for a moment mean to say that cock-fighting is not a brutal sport, for from the point of view of the onlooker it is; but I do say that from the animal’s point of view cock-fighting is far less cruel than coursing. I have no doubt that few people will agree with me, but at any rate let me plead for fairness in all sport; for without it so-called sport degenerates into cold-blooded murder.

This was a particularly late season for leverets, and I found one in November, which I kept until it was strong enough to take care of itself, as they were being killed all over the country. It was a very lean and scraggy youngster, much darker in colour than Bunty, and with no star on its forehead. The two had great games together, and the way Bunty patronised it was most amusing. The baby annoyed him dreadfully at times by persisting in thinking he was its mamma; it also went through the same exercises of turning and twisting, but since I let it go I have not seen it.

The two deep marks are the hind feet, the two smaller the fore feet. If the hare had not been running the fore feet would have only made one imprint together

I was asked the other day if I had discovered any hare “language.” Bunty makes a wheezing noise like a pug dog when he wants to be petted, and I am convinced that it is a sign of affection. The only other noise he utters is quite natural; it is a sharp little click, which he makes with his tongue against the roof of his mouth, and can be easily imitated in the same way. He makes this noise if he is excited or impatient; when he wants to jump out of my arms and I will not let him go, he clicks several times, jerking his head about. That is the only” language” I have heard.

In conclusion, if anyone feels tempted to tame a wild leveret, one of the first rules is never to keep it in a damp place, to give it plenty of fresh air and exercise, with a good variety of food and grit. Bunty is, I fear, too fat, but he is in perfect health, with a coat like silk, and he considers himself the handsomest hare in Ireland.

[Since this article was written we have received a sad letter from Miss Bland announcing poor Bunty’s death. He broke his leg so badly when playing in the greenhouse that it was found necessary to destroy him. ed.]

- Comments(0)